Karla McLaughlin drove all the way to my home to deliver this 15 pound organic-fed, free-roaming turkey and two pork loins. She generously took the time because I was in a pinch, facing a party deadline. She is a one-of-a-kind farm owner. Knowledgeable, caring and meticulously strict about raising the turkeys and other animals that she and her husband, John, tend on their farm.

Karla McLaughlin drove all the way to my home to deliver this 15 pound organic-fed, free-roaming turkey and two pork loins. She generously took the time because I was in a pinch, facing a party deadline. She is a one-of-a-kind farm owner. Knowledgeable, caring and meticulously strict about raising the turkeys and other animals that she and her husband, John, tend on their farm.They call it "Olde World Farms" and it is located in Montgomery, Texas. No antibiotics, no animal products in their feed. The turkeys stay inside large barns until they are big enough so that the hawks won't swoop them up. Then they grouse around and eat freely on the farm. You can contact Karla or John at (936)-597-3999. Their email is owf@oldeworldfarms.com.

To prepare the turkey for smoking, this is what I used to make the

Brine:

3 gallons warm water

1 lb salt

12 ounces light brown sugar

1 Tbs onion powder

1 Tbs garlic powder

Stir until the sugar and salt have completely dissolved then let the brine cool down completely.

Method:

1. I used a syringe to inject some of the brine into the meat. the total amount of brine should be 10% of the weight of the turkey. Here's the math for a 15 lb turkey.

15 X 16 ounces = 240 ounces

240 ounces X .10 = 24 ounces of brine. (FYI: One fluid ounce of water weights exactly 1 ounce)

2. Using a plastic or stainless steel container, submerge the turkey in the brine and refrigerate for 3 days. The container was too heavy and large for my refrigerator so I partially filled a large ice chest with ice and a little water and set the container in it. Closing the ice chest, the temperature is maintained at a safe 37-39 degrees F

3. After the third day, remove the turkey from the brine, rinse it thouroughly with fresh water, pat dry and place in the fridge, uncovered, for 16 hours until a pellicle forms on the skin. This tacky glaze will help absorb smoke and keep in the moisture. I hate to say this but in the interest of efficiency, omit this step if you don't have time to do this or if there's no room in the fridge.

4. Smoke the turkey in Pecan wood at 185 F for about 6-8 hours until the internal temperature reaches 165 F.

Ok, yes, you can enjoy a beer meanwhile, and ponder this:

A) The habit of cooking and eating turkey predates us by centuries and

B) The bird came from Mexico and is native to this land, Americas.

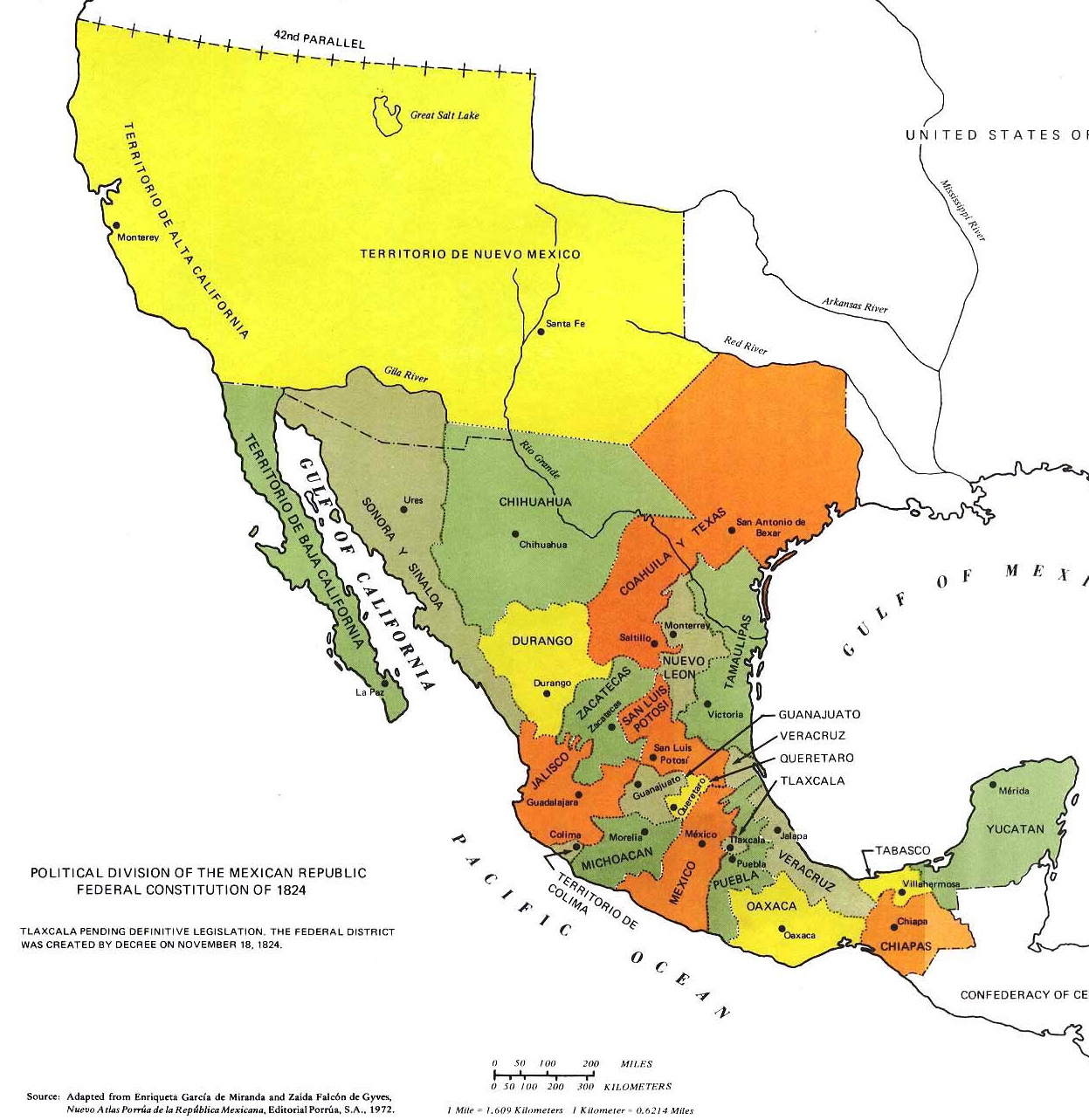

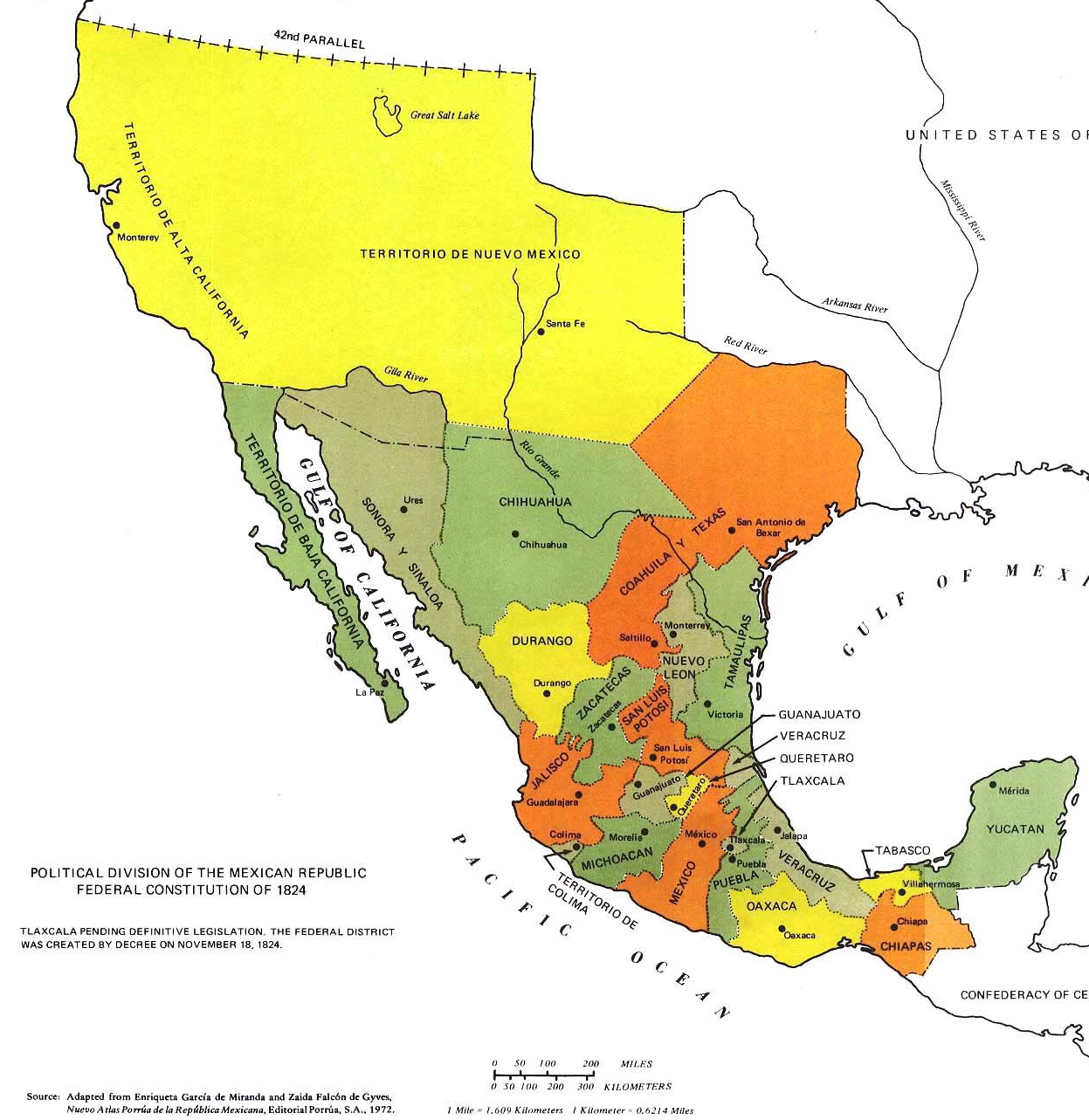

I've placed a dot on the location of Coba, Mexico, near Cancún.(1) This is where archeologists have found the earliest evidence of turkey remains. They are dated 100 BCE-100 CE. From there the turkey went north and populated North America, evidence of the vibrant trade and communication withiin the region pre-1400's. By the time the Spaniards arrived in Mexico, we had domesticated turkeys not just in Mexico but also in what is now the US New Mexico and Texas. Thereafter the turkey, wild and domesticated, populated the whole of the US and some of Canada. By your second beer, you will have pondered that we and the turkey go back a long way.

I've placed a dot on the location of Coba, Mexico, near Cancún.(1) This is where archeologists have found the earliest evidence of turkey remains. They are dated 100 BCE-100 CE. From there the turkey went north and populated North America, evidence of the vibrant trade and communication withiin the region pre-1400's. By the time the Spaniards arrived in Mexico, we had domesticated turkeys not just in Mexico but also in what is now the US New Mexico and Texas. Thereafter the turkey, wild and domesticated, populated the whole of the US and some of Canada. By your second beer, you will have pondered that we and the turkey go back a long way. Let me know how it turns out if you decide to smoke for Thanksgiving. ¡Feliz Día de Dar Gracias!

(1) map used by permission of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

1. Add the salt, sugar and spices to the water and bring to a boil, stirring to dissolve the salt and sugar completely.

1. Add the salt, sugar and spices to the water and bring to a boil, stirring to dissolve the salt and sugar completely. The recipe that I'm posting today is one for chefs and foodies. We will continue to serve food when needed to support Occupy Wall Street rallies. We will blog about food and it's corporate control. Foodies will take up anew conversations about the food movemen and about: Native Americans denied the right to plant corn seeds in their gardens because Monsanto has patented the seed, Obesity resulting from corporatized food,,etc., etc., etc.

The recipe that I'm posting today is one for chefs and foodies. We will continue to serve food when needed to support Occupy Wall Street rallies. We will blog about food and it's corporate control. Foodies will take up anew conversations about the food movemen and about: Native Americans denied the right to plant corn seeds in their gardens because Monsanto has patented the seed, Obesity resulting from corporatized food,,etc., etc., etc.

Toltec art and the huge monuments are well-known and iconic of MesoAmerica, but a lesser known fact is that the region has a delicious, distinctive cuisine. "Ajo Comino de Gallina" is a Hidalgo dish that uses poaching as a method for infusing flavors into food as it cooks with no fat. The French have a similar method, their Court Bouillon used to deep poach foods.

Toltec art and the huge monuments are well-known and iconic of MesoAmerica, but a lesser known fact is that the region has a delicious, distinctive cuisine. "Ajo Comino de Gallina" is a Hidalgo dish that uses poaching as a method for infusing flavors into food as it cooks with no fat. The French have a similar method, their Court Bouillon used to deep poach foods.

7. While the onions are cooking, grind the Serrano chile into a fine paste using a molcajete. Add a little of the strained broth to the molcajete to lift off the paste and add to the onions.

7. While the onions are cooking, grind the Serrano chile into a fine paste using a molcajete. Add a little of the strained broth to the molcajete to lift off the paste and add to the onions.

Recipe makes 25 small gorditas like the ones in the picture

Recipe makes 25 small gorditas like the ones in the picture

Tierra Caliente serves Mexican barbacoa tacos. Mexican "barbacoa" is beef. It has a long history in this region. It can be cooked underground (cabeza de pozo--barbacoa de cabeza) or, as the chef, María Zamano, does, on the stove with seasonings that include garlic and. I promised her I would not talk out of school so you'll have to ask her for her delicious recipe.

Tierra Caliente serves Mexican barbacoa tacos. Mexican "barbacoa" is beef. It has a long history in this region. It can be cooked underground (cabeza de pozo--barbacoa de cabeza) or, as the chef, María Zamano, does, on the stove with seasonings that include garlic and. I promised her I would not talk out of school so you'll have to ask her for her delicious recipe.  This is very different from taco combinations that simply "juxtapose" ingredients inside a tortilla. Tierra Caliente recipes harmonize. No clashing juxtapositions here. In order to accomplish this you have to know your past, both written and oral stories, and taste it. It makes for a fuller dining experience.

This is very different from taco combinations that simply "juxtapose" ingredients inside a tortilla. Tierra Caliente recipes harmonize. No clashing juxtapositions here. In order to accomplish this you have to know your past, both written and oral stories, and taste it. It makes for a fuller dining experience. To do this he has the right blend of egg yolks, butter, lemon and seasonings. The emulsion is whisked together so well that the mouth-feel is sooooo velvety. OK, I'll stop drooling. .. And he adds a twist that is his very own, a type of red chile!

To do this he has the right blend of egg yolks, butter, lemon and seasonings. The emulsion is whisked together so well that the mouth-feel is sooooo velvety. OK, I'll stop drooling. .. And he adds a twist that is his very own, a type of red chile!

Method:

Method:

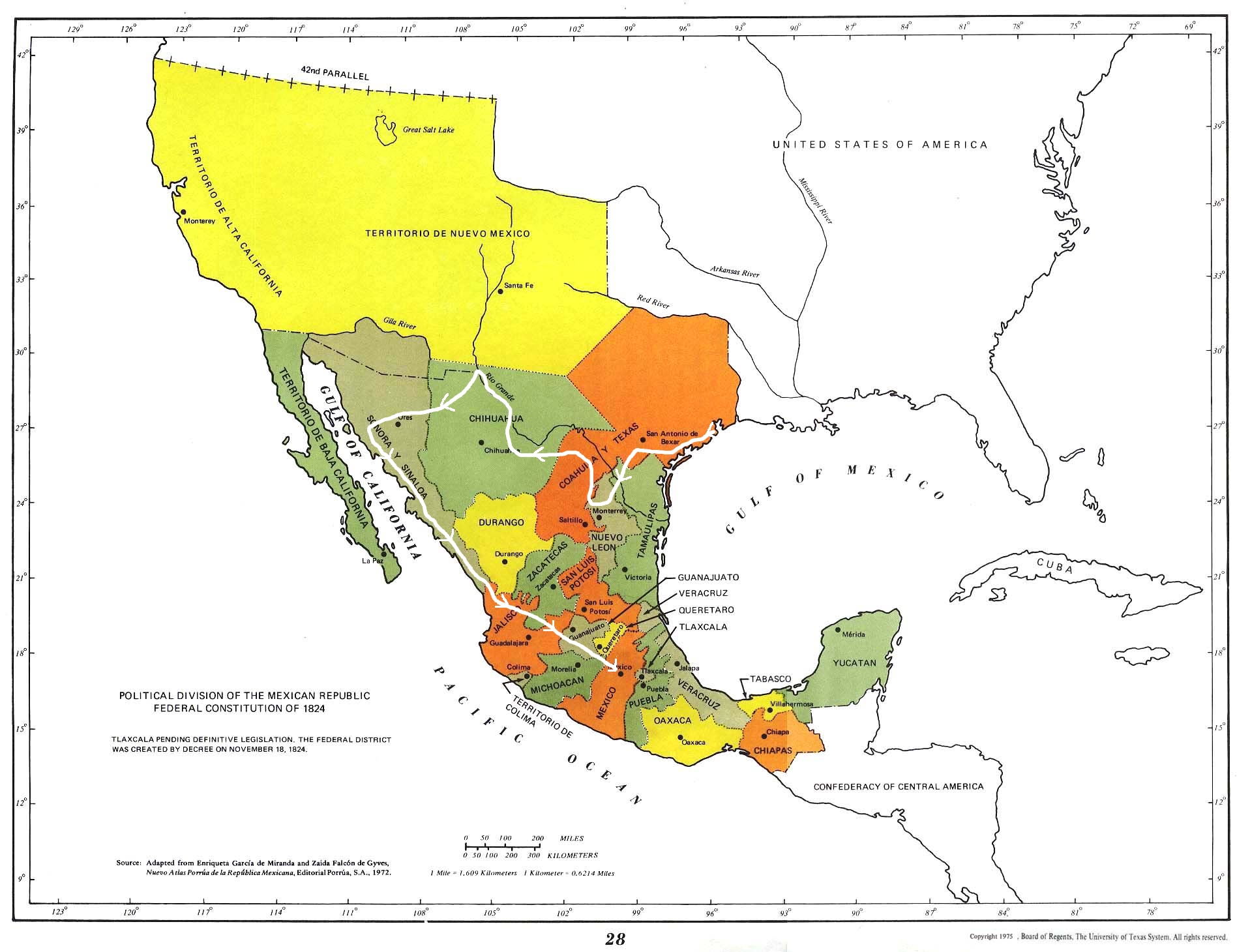

In the Mexican constitution of 1824, the republic of

Mexico included "Coahuila y Texas" as one state. (1) It extended

far North and South of the Rio Grande river which at that time was used in the region for transportation and irrigation.

In the Mexican constitution of 1824, the republic of

Mexico included "Coahuila y Texas" as one state. (1) It extended

far North and South of the Rio Grande river which at that time was used in the region for transportation and irrigation.

Indeed, on this map of 1824 Mexico(1) I drew the route that Cabeza de Vaca followed in 1500's to travel from Galveston to Mexico City. I traced the white line to show that, as the natives did at the time, he traveled from Galveston all through Sinaloa. (I based this route on the one researched and drawn by Alex D. Krieger, University of Texas Press) There were other similar travel routes that made it commonplace to exchange cooking techniques and ideas.

Indeed, on this map of 1824 Mexico(1) I drew the route that Cabeza de Vaca followed in 1500's to travel from Galveston to Mexico City. I traced the white line to show that, as the natives did at the time, he traveled from Galveston all through Sinaloa. (I based this route on the one researched and drawn by Alex D. Krieger, University of Texas Press) There were other similar travel routes that made it commonplace to exchange cooking techniques and ideas.

This fried fish method is straightforward and reflects the penchant for coupling the flavors of fish with corn, that elemental grain that was everywhere, even in our creation myths, all the way down to what is today Southern Mexico.

This fried fish method is straightforward and reflects the penchant for coupling the flavors of fish with corn, that elemental grain that was everywhere, even in our creation myths, all the way down to what is today Southern Mexico. Mayonnaise Sauce: makes one cup (I love this remoulade sauce. The French arrived in Texas in 1600's)

Mayonnaise Sauce: makes one cup (I love this remoulade sauce. The French arrived in Texas in 1600's)

When our European ancestors, searching for India, landed instead in South America and found chiles, they used the default name with which they were familiar, "pepper." They also called the South American natives "Indians," but that's another story.

When our European ancestors, searching for India, landed instead in South America and found chiles, they used the default name with which they were familiar, "pepper." They also called the South American natives "Indians," but that's another story. In my opinion, achieving the correct flavor profile of Carne Guisada depends entirely on what you grind in your Molcajete. The following recipe is my family's variation and of course I love it, but you can refine it according to your taste. Just remember that the focus should be on your Molcajete: the mixture of ingredients to include cumin, garlic and BOTH pepper and chiles.

In my opinion, achieving the correct flavor profile of Carne Guisada depends entirely on what you grind in your Molcajete. The following recipe is my family's variation and of course I love it, but you can refine it according to your taste. Just remember that the focus should be on your Molcajete: the mixture of ingredients to include cumin, garlic and BOTH pepper and chiles.  Let me know how this recipe turns out for you. ¡Buen Provecho!

Let me know how this recipe turns out for you. ¡Buen Provecho!

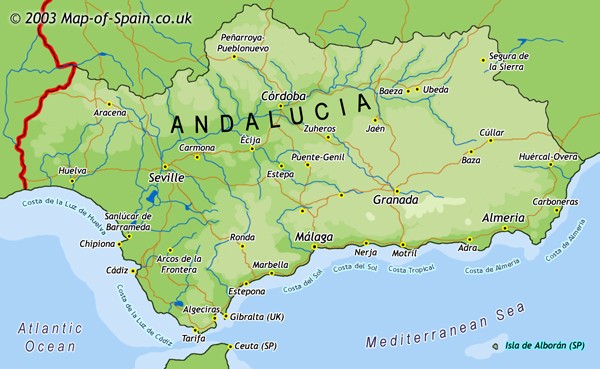

Within these boundaries Gazpacho has as many variations as there are Spaniards with opinions.

Within these boundaries Gazpacho has as many variations as there are Spaniards with opinions.

I think mole is becoming more available in Texas and Northern Mexico because of digital media and travel. Travel routes connecting today's Texas, Northern Mexico and Southern Mexico date back to the Texas Indians prior to the 1400's. The Mexico-US "Camino Real" of the Spaniards, was built upon one of these routes. These ancient routes enabled our native ancestors to learn about each other's cuisines (types of chiles, corn, cooking utensils, pottery, types of beans). With today's digital media I can blog. I think this accelerated sharing will increase the presence of Mole Poblano on our tables here in Texas and Northern Mexico.

I think mole is becoming more available in Texas and Northern Mexico because of digital media and travel. Travel routes connecting today's Texas, Northern Mexico and Southern Mexico date back to the Texas Indians prior to the 1400's. The Mexico-US "Camino Real" of the Spaniards, was built upon one of these routes. These ancient routes enabled our native ancestors to learn about each other's cuisines (types of chiles, corn, cooking utensils, pottery, types of beans). With today's digital media I can blog. I think this accelerated sharing will increase the presence of Mole Poblano on our tables here in Texas and Northern Mexico.

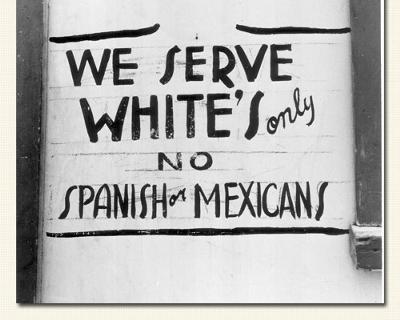

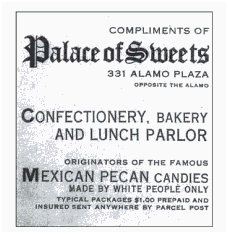

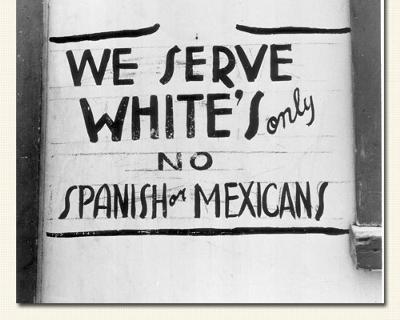

The picture above is from around 1915's -20's. It appears in the book chronicling segregation of Mexican-Americans, "A Place At The Table," by Maria Fleming (p.97).

The picture above is from around 1915's -20's. It appears in the book chronicling segregation of Mexican-Americans, "A Place At The Table," by Maria Fleming (p.97).

To reject each other. To celebrate each other.

To reject each other. To celebrate each other.  It's not that we don't think black beans are delicious It's simply that for our cuisine they are philosophically incorrect. By this I mean that they are incoherent, out of context and clash with both the techniques of cooking and the complementary flavors of local products, the terroir.

It's not that we don't think black beans are delicious It's simply that for our cuisine they are philosophically incorrect. By this I mean that they are incoherent, out of context and clash with both the techniques of cooking and the complementary flavors of local products, the terroir. I like the following paragraph from the University of North Texas College of Arts and Sciences "The Philosophy of Food Project."

I like the following paragraph from the University of North Texas College of Arts and Sciences "The Philosophy of Food Project."

Our region is called the Coahuiltecan Region (Just N & S of the Rio Grande River) and I'm proud to say that our indigenous recipe is as delicious as ever!

Our region is called the Coahuiltecan Region (Just N & S of the Rio Grande River) and I'm proud to say that our indigenous recipe is as delicious as ever!

I'm with Mark Twain who lambasted the Catholic church in his early years but later was more accepting and understanding yet cool. I like Mark Twain because he is said to have once proclaimed, "Too much of anything is bad, but too much champagne is just right."

I'm with Mark Twain who lambasted the Catholic church in his early years but later was more accepting and understanding yet cool. I like Mark Twain because he is said to have once proclaimed, "Too much of anything is bad, but too much champagne is just right." He is a lover of Tex-Mex food and has done a big service to this regional cuisine by researching and documenting its evolution from ca.1700's. Kudos to him!! Especially since he's had the temerity to kindly and respectfully critique writers like Diana Kennedy who make Mexico the source and the frame of reference for Tex-Mex.

He is a lover of Tex-Mex food and has done a big service to this regional cuisine by researching and documenting its evolution from ca.1700's. Kudos to him!! Especially since he's had the temerity to kindly and respectfully critique writers like Diana Kennedy who make Mexico the source and the frame of reference for Tex-Mex.  These 3 Mexican Candies exemplify aspects of the 500-year-encounter between European and Latin American cuisines. Starting at the left and going clockwise they are: Dulce de Camote, Dulce de Leche Quemada and Mazapán.

These 3 Mexican Candies exemplify aspects of the 500-year-encounter between European and Latin American cuisines. Starting at the left and going clockwise they are: Dulce de Camote, Dulce de Leche Quemada and Mazapán.